Whether in print, on CD-ROM or on the internet, case law in one form or another has been around for generations, but the essential methods of using it haven’t changed that much over the centuries.

Backed up by legislation where it exists, we predominantly continue to rely on official law reports, regardless of the methods used both to identify them and to check the current validity of the precedents they set. This status quo continues to be supported by many of the prominent players in the legal information market.

But a new standard in legal research is starting to emerge and we at Justis Publishing are aiming to be at the forefront of this movement.

Innovations across the internet beyond the law are starting to shake up what’s available for free, something that’s slowly beginning to apply as much to the law as to other subject areas.

This is happening with judgments from the higher courts around the common law world. It’s happening with legislation. And it’s happening with legal commentaries and blogs.

But with general search engines alone, it’s impossible to prioritise your research with so much un-marshalled content to wade through.

Interpreting and absorbing data is becoming more important than simply accessing it, and this is where people will start to place the greatest value in their legal research tools.

It is therefore our profound view at Justis Publishing that data proliferation and smart technology, engineered to help people harness, interpret and analyse this data, will soon converge to bring consumers a truly 21st-century legal research experience. This is something that we’ve felt confident enough to invest in heavily over the past few years to help accelerate the process.

And it’s actually been happening for a while. The British and Irish Legal Information Institute (BAILII) has provided access for free to judgments from most of the higher courts from 1996 onwards. Often complemented by our JustCite citator, BAILII is a noble service that’s increasingly used as a starting point by legal researchers. Other countries’ legal information institutes have taken similar journeys, many of which we work with for the good of the common law.

But we’ve gone further. Having scanned numerous hard-copy collections and processed hundreds of millions of pages of transcripts to put on to our Justis legal library in the past few years, we now offer higher court judgments for civil and criminal law from England and Wales that go back to 1951 and 1963 respectively, comprising 221,000 documents at the last count, which is many, many times the number of law reports for the same period. And we’re also gathering similar material from Australia, Canada and beyond.

Though all non-copyrighted and technically free to anyone who can lay their hands on them, without these data-capture projects, much of the material – some of it previously available only behind lock and key in dusty basements – would otherwise be prohibitively difficult and costly for end-users to track down on their own.

Used in conjunction with JustCite and alongside more established law report series, intuitively searchable databases of case law such as that on Justis can help fill important gaps in otherwise missed precedent.

Law reports still have their place. But the emphasis is beginning to change.

As well as capturing all of this primary authority, we’re working on ways of combining input from our legally qualified editors with the rapidly developing smart technologies at our disposal, the focus being to hugely enhance the metadata and visualisation tools that stitch this full-text material together and set it in a digestible context.

We haven’t assembled all the pieces in the jigsaw of our new legal research platform, which we’re calling JustisOne and which will initially operate alongside Justis and JustCite. But a picture is slowly surfacing.

Our excitement stems both from the data itself and from what we’re doing with it.

As outlined above, the data is an extension of what we’ve already loaded on to Justis – primary authorities from around the common law world, which we’ll follow with legislation.

Interwoven with these case law records is a complex, 14-level taxonomy of legal subject terms, keywords and phrases, which are inferred semi-automatically from the full text of the cases by the taxonomy tables we’ve built and the algorithms that drive them.

The goal is to give users much more power when searching by these terms, and it will also convey far greater meaning when looking at the terms, which will be attached to the finely ranked cases that they see in their search results.

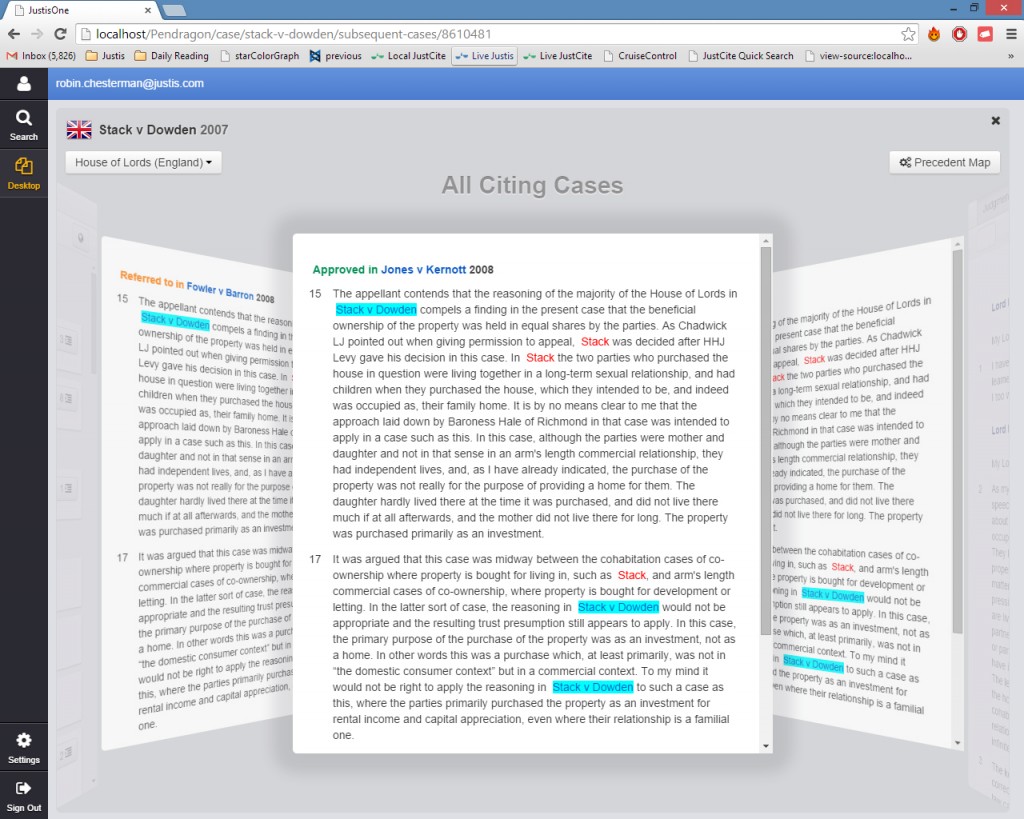

Users of JustisOne will also see references to citing cases and, importantly, the paragraphs that they cite; useful in their own right and enhanced greatly by the plans we have for displaying them on our new platform in what we’ve started to quaintly describe as a rolling carousel of subsequent judgment paragraphs – very much a working title!

A reworked precedent map will also feature on JustisOne.

But arguably the most exciting plan we have is to semi-automatically draw out the most cited paragraphs of all cited cases.

Let’s look at that again because it’s easy to get tangled in knots with this sort of thing.

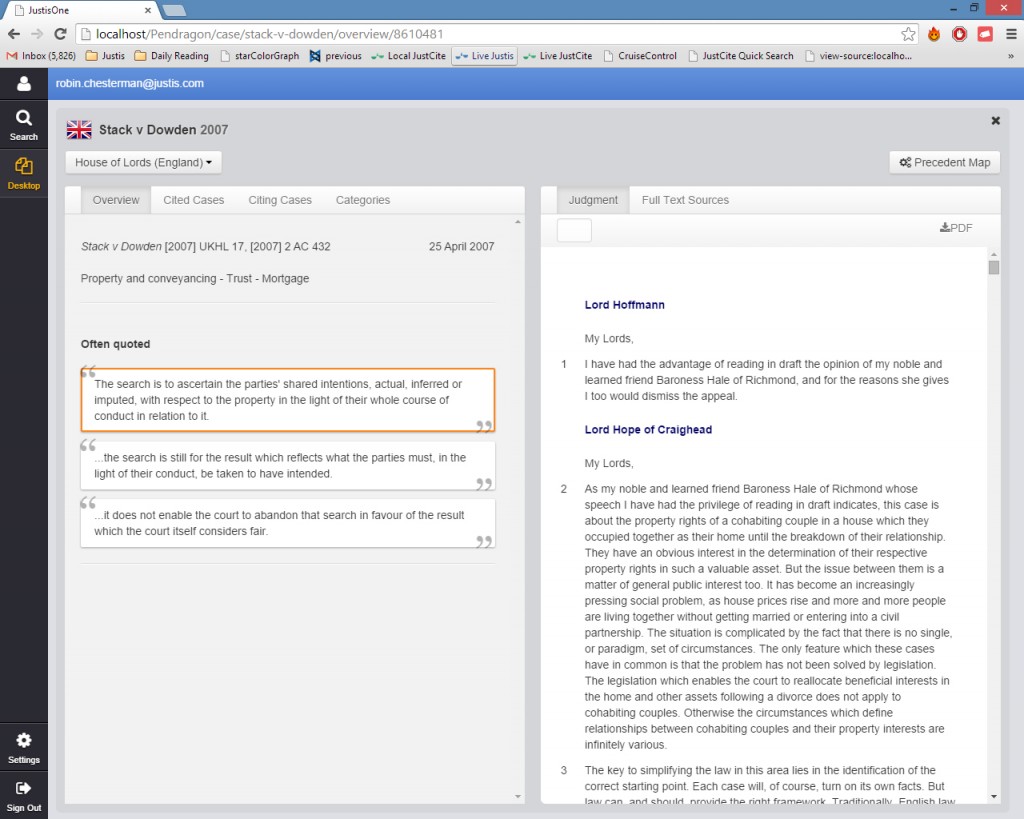

Take Stack v Dowden, which considered beneficial property ownership. It would take an almighty effort to manually identify that the most cited paragraph in its judgment is “The search is to ascertain the parties’ shared intentions, actual, inferred or imputed, with respect to the property in the light of their whole course of conduct in relation to it”. But doesn’t that just sum up the essence of the case?

Combine it with the second and third most cited paragraphs – “First, it emphasises that the search is still for the result which reflects what the parties must, in the light of their conduct, be taken to have intended” and “Second, therefore, it does not enable the court to abandon that search in favour of the result which the court itself considers fair” – and living, breathing clarity on the case rises from the page, something we’ll deliver on the service by modelling patterns and frequencies of phrases on the fly across of the hundreds of citing cases.

We’ve found ourselves starting to call these “power paragraphs” internally, a faintly ridiculous name. Far better is “retrospective headnotes,” as a preeminent QC we showed a prototype to enthusiastically labelled them recently.

It hadn’t quite dawned on us that that’s what they could eventually become but we think he’s right.

After all, the headnotes of traditional law reports tend to be written at much the same time as the cases themselves, give or take. And they’re not updated. But these “power paragraphs” are more an ever-evolving distillation of how the case has been applied since.

In time, retrospective headnotes could become a better guide for determining the currency and potential application of a precedent than traditional headnotes – not to mention that they potentially apply to all judgments, not just those selected to appear in reported series.

Granted, those that have been reported will, for the time being, remain more likely to be cited but it won’t be their exclusive preserve, and once an unreported case is cited, its likelihood of further citation increases.

Furthermore, this methodology will also usefully highlight elements of cases that were reported but build up subsequent citations for other reasons, an analogy being Pepper v Hart, which went to court to deal with an obscure question of tax but set a celebrated precedent on examining pre-legislative discussions to determine the spirit rather than the letter of the law.

And it’s only really the start. Now we’ve gathered together our own extensive and ever-growing collection of data, we’re free to do with it what we like. We have fewer dependencies. We can build exciting new graph databases, establish new and intriguing data relationships and move legal research away from “document delivery” towards something alive, evolving and ever-refining the shape of the law.

That’s a new standard in legal research that we’re keen to be a part of.

We might not have reached that tipping point quite yet but if you want to contribute to the iterative design process of JustisOne, please email me at alistair.king@justis.com.

With an academic background in engineering, Alistair King has spent most of his professional life in book publishing, journalism and electronic legal publishing. The marketing manager at Justis Publishing, where he has worked since 2007, he has learnt about the law, technology and legal research on the job, and has interviewed scores of practitioners and librarians over the years. He blogs alongside his colleagues on a wide range of topics at http://blog.justis.com.

One thought on “A new standard in legal research”

Comments are closed.