Sunburst: a moment of reckoning

Towards the end of 2020, the National Security Agency (NSA) issued a warning, claiming that “Russian state-sponsored malicious cyber actors” had essentially hacked into a piece of network management software belonging to SolarWinds, which was installed on networks belonging to US government agencies and almost all Fortune 500 companies. Following discovery of this hack, dubbed Sunburst, the US department of Homeland Security promptly ordered all federal agencies to disconnect from the platform.

According to the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency (CISA), the hack began in at least March 2020, and those responsible had “demonstrated patience, operational security, and complex tradecraft”. It warned that the sophisticated hack posed “a grave risk to the Federal Government and state, local, tribal, and territorial governments as well as critical infrastructure entities and other private sector organizations.” In effect, the perpetrator had really shaken up both the American state and many of its biggest private corporations, along with a smaller number of organisations outside the US including in the UK.

In a blog post, Microsoft President Brad Smith said that the Sunburst hack signified a “moment of reckoning” and that it was crucial to take “stronger steps to hold nation-states accountable for cyberattacks”. He warned that mercenary-style technology companies, known as private sector offensive actors (PSOAs), are increasingly selling their products and services – which primarily involve sophisticated computer hacking – to nation states, and he urged the Biden-Harris administration to weigh in on the related legal dispute between WhatsApp and the Israeli based NSO Group. He also noted that, while health systems were already under immense pressure from the biological virus of Covid-19, cyberattackers were using computer viruses to target “hospitals and public health authorities, from local governments to the World Health Organization (WHO).”

A virtual cold war?

Whilst most cyberattacks have a financial motive, there’s increasingly a geopolitical angle at play. The WannaCry ransomware attack of 2017, which caused some NHS trusts to postpone operations, was seemingly a straightforward piece of malware designed to enrich cybercriminals with Bitcoin spoils. But the UK and US governments believed it originated from North Korea, indicating a potential state sanctioned attack. Meanwhile, the “emailgate” affair, which involved a hack on Hillary Clinton’s email server, purportedly by a proxy of a Russian intelligence agency known as Fancy Bear, was thought by some commentators to constitute foreign interference in the 2016 US presidential elections.

It is always difficult to definitively establish whether a cyberattack was orchestrated by a nation state. The rather anarchic nature of the internet and the lack of regulation means that it’s easier for governments to cover their tracks online, compared to state-sanctioned real world attacks on foreign soil (eg the Skripal, Litvinenko and Khashoggi affairs).

But the rise of the Internet of Things and Smart Cities is increasingly exposing critical national infrastructure, such as electricity grids and water treatment plants, to the possibility of serious cyberattack by foreign powers. Financial institutions are similarly vulnerable, as was seen recently in the hack of New Zealand’s central bank. The British government is suitably worried about potential interference from the Chinese state that, following advice from the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) and amid pressure from the US, it vowed to remove Huawei equipment from 5G networks by the end of 2027, and has introduced the Telecommunications (Security) Bill to this effect.

Trident vs Trojan

The UK government recently announced, in its Integrated Defence Review, that it was lifting the cap on the number of Trident nuclear warheads it can stockpile, from 180 to 260. It also stated that it reserves the right to use its enhanced nuclear arsenal if threatened by “emerging technologies” which could have a comparable impact to weapons of mass destruction. Certain press outlets have concluded that this means the UK would consider a nuclear retaliation against a serious cyberattack orchestrated by an enemy state – although this is not actually mentioned anywhere in the report.

It is worth stating that the Defence Review does include a section entitled “Responsible, democratic cyber power” which notes the establishment of the National Cyber Force (NCF) in 2020. It also says that that government plans to publish a new cyber strategy in 2021, under which it will seek to bolster cybersecurity and ensure that the UK is able to “withstand and recover from cyber-attacks.” So, although shoring up the nuclear deterrent is arguably little more than posturing, it would be unfair to say the government is complacent about the threat of state sponsored hacking.

How lawyers can help

The interplay between geopolitical hacking may not, at first glance, appear to fall within the purview of an average lawyer. But if we consider that one of the priorities of in-house counsel is the minimisation of business exposure to risk, it is clear that the prevention of cyberattacks – whether by a nation state or a teenage chancer – is within their remit. For example, the fact that 39 per cent of businesses have reported cyber security breaches or attacks in the past 12 months, whereas only 23 per cent have a cyber security policy covering home working, is a sign that more robust employment law advice is required in the majority of companies.

Both in-house lawyers and any firms providing advice to public, private and third sector organisations, should be aware of the acute threat of cyberattacks. And they need to ensure their clients are sufficiently protected; this should not simply be left to the IT department, since the financial and reputational fallout goes far beyond any potential damage to IT infrastructure. In light of the growing spectre of state sponsored malicious hacks, lawyers should also be particularly attuned to any political dimension of their clients and shore up defences accordingly.

Further reading

US Department of Homeland Security: Geopolitical Impact on Cyber Threats from Nation-State Actors (PDF).

Alex Heshmaty is technology editor for the Newsletter. He runs Legal Words, a legal copywriting agency based near Bristol. Email alex@legalwords.co.uk. LinkedIn alexheshmaty.

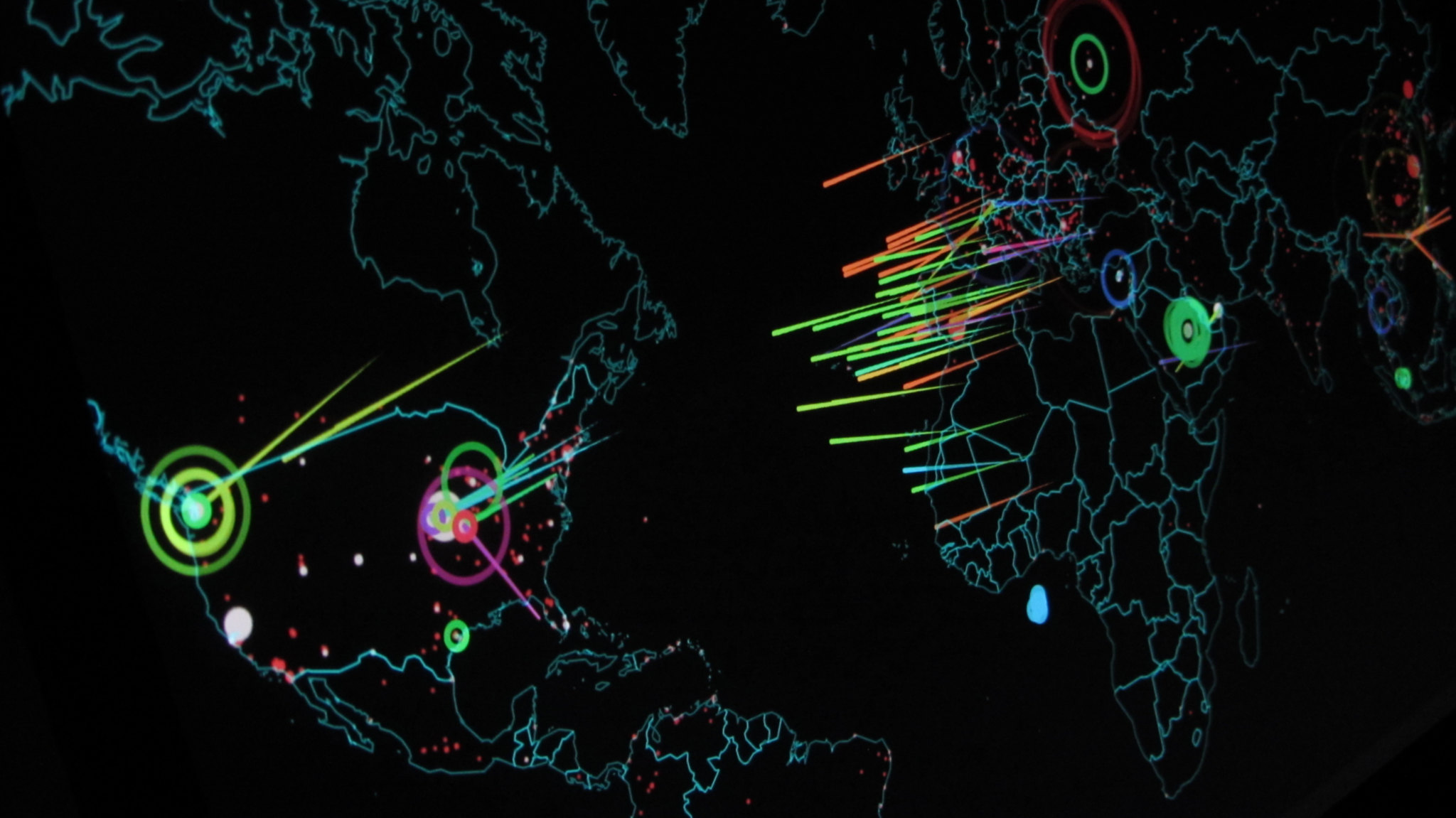

Image cc by-sa via Christiaan Colen on Flickr. Taken from the Norse Attack Map.